Radiative feedback matters for the initial mass function of metal-poor stars

Title: Impact of radiative feedback on the initial mass function of metal-poor stars

by Guan-Fu Liu | Jan 6, 2024 | Daily Paper Summaries |0 comments

Authors: Sunmyon Chon, Takashi Hosokawa, Kazuyuki Omukai, Raffaella Schneider

First Author’s Institution: Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany

Status: Submitted to MNRAS [open access]

Initial mass function (IMF) is fundamental to our understanding of the formation and evolution of galaxies. IMF is directly related to star formation, stellar evolution, chemical enrichment, feedback processes, and almost all observable properties of galaxies. IMF describes the distribution of stellar masses during a single star-forming episode when the stars are at the zero-age main sequence (ZAMS), i.e., when stars enter the main sequence and start hydrogen burning. Mathematically, IMF is defined as the number of stars per unit mass interval,

where

The first form of the IMF was introduced by Salpeter in 1955, which is a power law with a slope of

which is now known as the Salpeter IMF. There are also other kinds of IMF such as the Chabrier IMF and the Kroupa IMF. Although there are some differences between these IMFs, they are all universal, i.e., independent of the environment. It should be noted that such universality is not intuitive, but the observations of the Milky Way and nearby galaxies have shown no convincing evidence for the variation of IMF. Since the determination of IMF for the high-redshift universe is challenging, the authors of this paper conduct a series of long-term hydrodynamic simulations to provide more insights into the IMF in the early universe.

A simple picture: Jeans instability

Before going into the details of the simulations, some basic concepts and mechanisms should be introduced. Jeans instability is the most important general picture for the formation of stars. Jeans mass is the minimum mass required for a cloud to collapse under its own gravitational force, which can be used to estimate the mass of the stars. The Jeans mass is given by

where

Star formation at different metallicities

To investigate the role that metallicity plays in star formation, the author conducts a series of simulations with varying metallicities. As is shown in Figure 1, the stars are more cluster-like at higher metallicities, but only a few stars are formed at the lowest metallicity. The expansion of HII regions created by massive stars disrupts the gas cloud and suppresses the star formation at all metallicities, which underlines the importance of radiative feedback.

Figure 1: The projected density, and temperature distribution at the epoch of the first protostar formation for $\text{[Z/H]}= $

Star formation history at solar metallicity

More details about the star formation history at solar metallicity are shown in Figure 2. The star formation history can be divided into four epochs, which goes as follows,

- Epoch A: there is a fragmentation of a filamentary cloud, and hence protostars are formed in alignment. But no massive stars have been formed yet.

- Epoch B: The protostars formed in epoch A have grown and the most massive one has reached

- Epoch B: The protostars formed in epoch A have grown and the most massive one has reached

- Epoch C: The HII region expands in all directions, but the gas hidden behind the filament is shielded from the ionizing photons and remains neutral.

- Epoch D: Almost all the domain is filled with the HII region, while there is still some dense and neutral gas deep inside the remaining filament. Compression of the cold and neutral gas by the HII region leads to the formation of new stars.

Figure 2: How the total stellar mass evolves with time, and the projected density, temperature, and the

Star formation history at extremely low metallicity

For the extremely low metallicity (

- Epoch A: The star formation sequence is distinct from the solar metallicity case. Since the metallicity is extremely low, the cooling is inefficient and the temperature is high, which eliminates the fine structure created by initial turbulence. The structure of the gas is more core-like and no filamentary structure is formed. Therefore, stars are formed within such a small cloud core, some of which may be ejected due to the gravitational interaction with other stars.

- Epoch B: Star formation is suppressed by stellar feedback and the HII region expands. In addition, the expansion of an

- Epoch B: Star formation is suppressed by stellar feedback and the HII region expands. In addition, the expansion of an

- Epoch C: Since the massive stars can be ejected to an outer region, the HII region expands and suppresses the star formation at the outer region. Such an ejection of massive stars is more common for the extremely low metallicity case, as the stars tend to be more concentrated in the center initially.

- Epoch D: The star-forming gas is completely depleted and the star formation is terminated.

Figure 3: Same as Figure 2, but for the extremely low metallicity (

Radiative feedback has an important impact on the star formation process and, thus on the initial mass function, at different metallicities. There are two different mechanisms for radiative feedback, that is dust heating and photoionization, which are discussed in the following.

Dust heating: fragmentation suppression

The heating of dust grains by stellar radiation hinders the fragmentation of the gas cloud at a small scale, reducing the number of low-mass stars with

Figure 4: The upper and lower panels illustrate the runs with stellar feedback and without feedback, respectively. The leftmost column show the distribution of the gas density at a large scale. The remaining two columns illustrate the zoom-in view of the gas density and temperature within the area marked by the white square on the left panels. Stars with masses higher (lower) than

Photoionization: hindrance of growth of massive stars

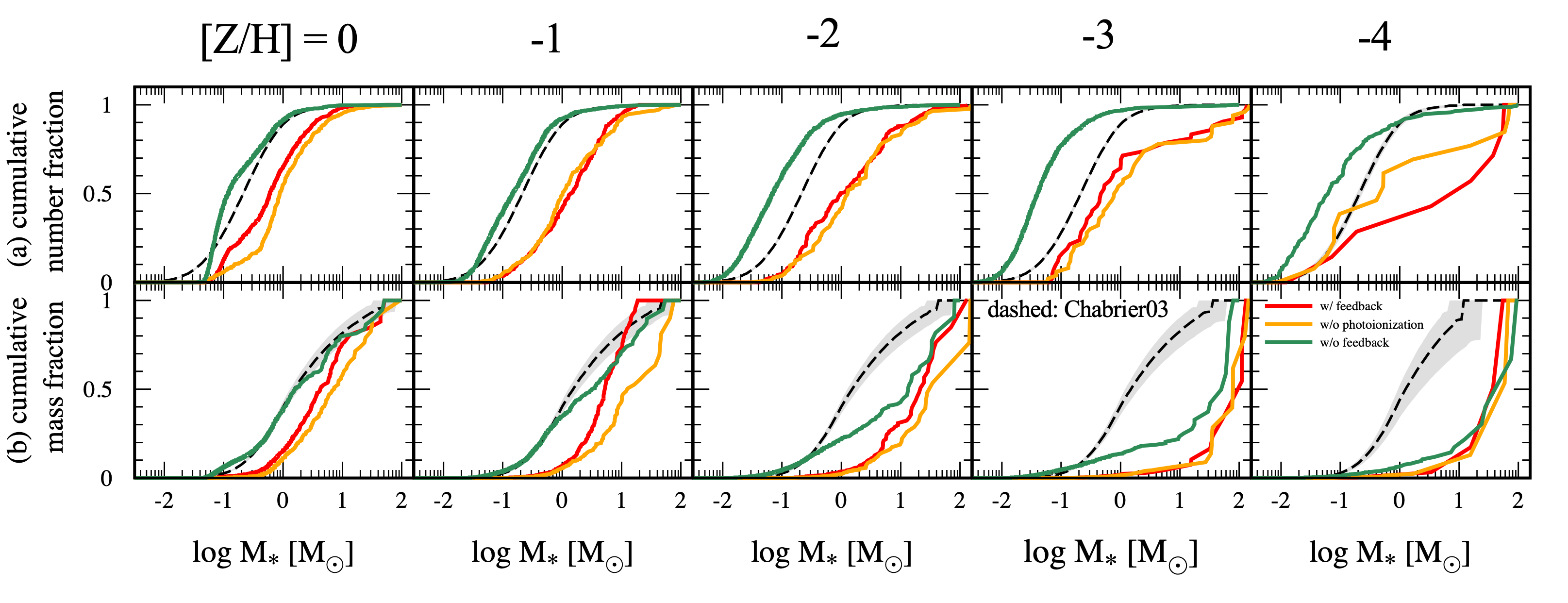

Photoionization is another important mechanism for radiative feedback, which has a substantial impact on the formation of massive stars, especially for the higher metallicities

Figure 5: The cumulative number (mass) fraction of stars with masses below

The overall shape of the IMF

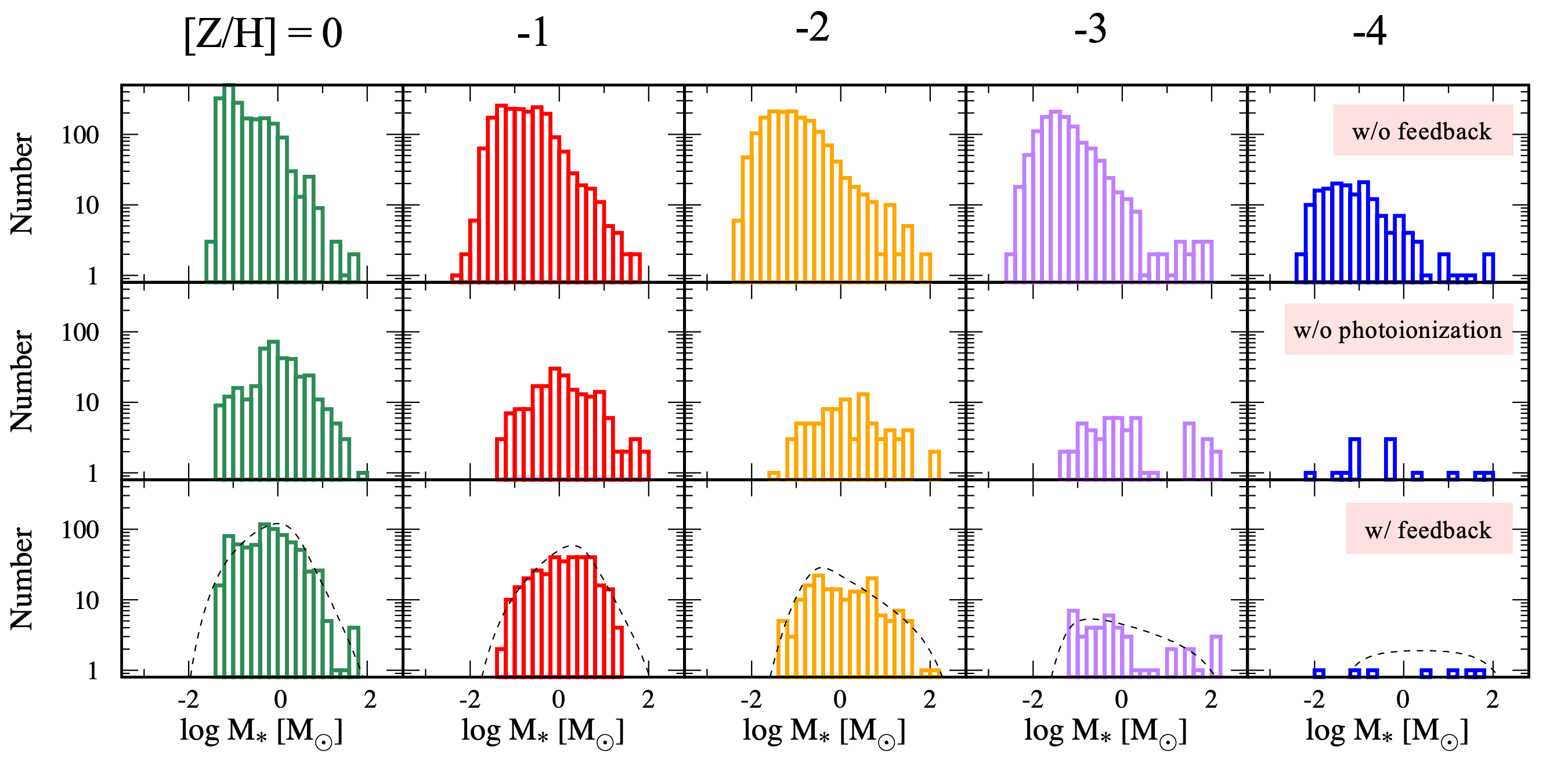

Since the radiative feedback has a significant impact on the formation of stars, with the dust heating suppressing the formation of low-mass stars and the photoionization suppressing the formation of massive stars, the overall shape of the IMF is changed. Figure 6 shows the stellar mass distributions at the end of simulations for different metallicities with

Figure 6: The stellar mass distributions at the end of simulations for different metallicities with

The authors conduct a series of long-term hydrodynamic simulations to investigate the impact of radiative feedback on the IMF at different metallicities. They find that radiative feedback matters in shaping the IMF at lower metallicities. The dust heating suppresses the formation of low-mass stars, while the photoionization suppresses the formation of massive stars. Since the metallicities in more pristine environments are lower, the radiative feedback is more important in the early universe. As the observation in the local universe suggests a universal IMF, this paper provides more insights into the possibility of the variation of the IMF.